CHAPTER THREE: RETAIL COMPETITION, CUSTOMER CHOICE AND CONSUMER PROTECTION

Introduction

This chapter addresses fundamental issues of retail competition, consumer choice and consumer protections specific to conditions in Nebraska. It examines wholesale supply pricing and other preconditions for retail competition. It outlines the interest of Nebraska consumers in "customer choice" and the regulatory structure and rules needed for consumer education and protection. It also offers the views and recommendations of the Advisory Group and the Task Force. In summary, the chapter outlines consumer-related elements that need to be in place if retail competition is to be established in the state.

Retail competition. the opening of an exclusive distribution system to competitive power suppliers. as it is proposed in most states offers an alternative to state regulation of energy pricing. Proponents of retail competition reason that competitive pressures to attract and keep customers can spark innovation in products, services, technology, and most importantly produce savings for consumers. As noted previously, such choice requires markets for wholesale and retail competition for energy supply. Establishing these competitive markets, in turn, may require restructuring of electric industry operations into separate distribution, transmission and generation entities. It also requires development of additional regulatory rules, standards, and policies, and physical and electronic business infrastructure to support competitive retail market activity.

Each state must evaluate the costs and benefits of a transition to a competitive retail market based upon its own unique conditions. Those conditions include the industry structure and governance, cost of energy supplies, and the character of its consumer base.

Conditions in Nebraska differ significantly from those of other states that are moving to establish retail competition. Nebraska is served exclusively by consumer-owned public power districts, municipal systems, and rural electric cooperatives. These systems deliver electricity as a non-profit "service" under principles of fair, just and non-discriminatory pricing. Equally important, they operate under the control of local boards.

In concept, this is far different than the market-based systems being proposed and developed in other states. Those markets are primarily focused on creating a competitive option to state-regulated energy pricing which does not exist in Nebraska. The purpose of competitive supply operations is to carry out private transactions with selected large customers

or selected customer groups with delivery of electricity as a "commodity" or "financial product." This is a striking contrast to principles of non-discrimination and universal service and non-profit rates offered on a transparent basis in Nebraska.

Prices and efficiency also show a strong contrast. As a general measure of the effectiveness of these systems, in 1997, the average retail price for Nebraska's commercial consumers was the 6th lowest in the nation (5.46 cents/kilowatt hour); industrial consumers were the 7th lowest (3.61 cents/kilowatt hour); residential consumers were the 9th lowest (6.38 cents per kilowatt hour). These rates are indicated on Maps M3-1, M3-2 and M3-3) As a further measure of the effectiveness of its consumer-owned electric systems, Nebraska anticipates no net stranded costs on a statewide basis; a primary transition issue in states with state electric utility regulation.

While most states taking aggressive action are attempting to reduce high electric costs, Nebraska faces the challenge of retaining its low costs. Nebraska's systems currently utilize lower cost electric energy and capacity than other electric utilities in the region, a condition expected to continue into the foreseeable future. Rather than a reduction of costs resulting from retail competition, Nebraska could experience an increase in power costs.

Three studies of national data have been conducted since 1996, two by federal agencies and a third by a national trade association, that indicate Nebraska consumers would receive little or no savings from a transition to retail competition. In addition, a draft study conducted by the USDA included Nebraska among the states that would experience net losses from establishment of retail competition.

Given the variation in these studies, the Nebraska Power Association conducted its own examination, looking specifically at anticipated wholesale power costs for the state and the region.

In both upper and lower price scenarios Nebraska's power costs are below those of the region. This is due to lower in-state production costs and low-cost purchased power contracts. Differences in retail electric rates for the state's electric systems are due primarily to variations in local fixed costs and accounting for the individual systems. (See Chapter 5 and Chart 5-1 for an illustration and discussion of projected wholesale power costs.)

While Nebraska's low wholesale power cost projections indicate an advantage to maintaining low priced non-profit, cost-of-service power supply, the industry and market will continue to evolve and changes in wholesale supply costs and pressures for retail choice may make it difficult or impossible for the Nebraska electric systems to maintain cost-based pricing and low-cost power supply. It is essential, therefore, to examine all costs and implications of retail competition, and to understand methods to assess potential benefits and protect Nebraska consumers.

Consumer Interest in Retail Competition and "Customer Choice" In Nebraska

As noted above, much of the driving force to establish competitive markets and restructure the electric industry is based on the concept that wholesale market competition and "customer choice" at the retail level will deliver benefits for consumers that cannot be gained under a regulated structure. "Customer choice" is generally taken to mean each individual metered customer having the ability to determine who their supplier of electric energy will be.

The concept of "customer choice" and the freedom it implies has substantial appeal to consumers. However, due to the practical matters of high transaction costs and low profit margins, "choice" and competitive access for small consumers remains an unrealized goal in states that have established retail competition. Market trends to "cherry-pick" and provide service only to large consumers, may delay or undermine access by small consumers for an indefinite period, if specific structures and rules are not put in place to address these trends. Even for those who receive access to "choice" the control and leverage offered may not be comparable to the leverage and control offered by a consumer-owned system. It has been generally accepted, based on experience in other service markets, that there will be "winners" and "losers" in retail electric markets. Despite the image of "customer choice" residential, small commercial consumers, and rural consumers could face a difficult time meeting their traditional desires for low costs, stable rates, reliability, and quality of service and receive new benefits from a competitive retail electric market.

Nebraska's total consumer base of 835,905 metered customers is made up of 82 percent residential consumers; 13 percent commercial; and approximately 5 percent industrial, irrigation and miscellaneous types. Nebraska's electric consumers can also be categorized as 81 percent "urban" and 19 percent "rural" if classified by service from predominantly "urban" or predominantly "rural" electric systems.

Table 3-1 Nebraska Retail Customers

|

STATE OF NEBRASKA--RETAIL | ||||||

|

Class of Consumers |

No. of Consumers |

% of Consumers |

Energy (MWH) |

% of Sale |

Revenues ($1,000) |

% of Rev. |

|

Residential |

687,214 |

82.2 |

7,564,902 |

37.0 |

$482,306 |

43.5 |

|

Commercial |

105,847 |

12.7 |

6,648,369 |

32.5 |

$339,276 |

30.6 |

|

Industrial |

2,368 |

0.3 |

4,775,113 |

23.4 |

$188,115 |

16.9 |

|

Irrigation |

31,569 |

3.8 |

749,624 |

3.7 |

$61,504 |

5.5 |

|

Other |

8,907 |

1.0 |

692,219 |

3.4 |

$39,049 |

3.5 |

|

TOTAL |

835,905 |

100.0 |

20,430,22727 |

100.0 |

$1,110,250 |

100.0 |

Source: L.R. 455 Survey

The total statewide energy sales to residential, commercial, and industrial customers in Nebraska for 1995 were 37 percent, 33 percent, and 23 percent, respectively, not including irrigation and miscellaneous other categories. As indicated in Table 3-1, the respective payments made by customers reflect the varied rates charged to each customer class. Based on "cost-of-service" formulas, larger customers generally have lower cost-of-service per kilowatt hour of consumption. Residential customers tend to have a higher cost-of service. (Rural customers tend to have the highest cost-of-service because of their lower density.)

In view of their greater numbers for consumption and cost, residential customers contributed 43 percent of revenue paid by all customer classes. Commercial and industrial customers followed with about 31 percent and 17 percent of revenues, respectively. All customers paid a total of $1.1 billion for electric service in 1995. Low power costs and customer statistics indicate that Nebraska's plan for retail competition would need to consider special measures to assure the opportunity for benefit for all customers.

Despite the relatively low level of industrial sales and a low customer density in much of the state, Nebraska's average electric rates compare very favorably to the region and the nation. Table 3-2 indicates that Nebraska has been maintaining the low costs discussed earlier for 1997.

Table 3-2 also shows that this finding holds for both Nebraska urban and rural utilities, as well as small and large systems.

Table 3-2 Comparative Average Energy Costs (Cents/KWH) 1995

|

ELECTRIC ENERGY COSTS (Cents per KWH) | ||||||

|

|

ALL SYSTEMS |

RURAL SYSTEMS | ||||

|

CLASS |

NEB. |

U.S. |

REGION |

NEB. |

U.S. |

REGION |

|

|

||||||

Residential |

6.4 |

8.4 |

7.5 |

6.2 |

7.6 |

7.4 |

|

Commercial |

5.1 |

7.7 |

6.2 |

6.1 |

-- |

6.6 |

|

Industrial |

3.9 |

4.7 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

-- |

4.6 |

|

Irrigation |

8.2 |

-- |

-- |

8.2 |

-- |

8.6 |

|

TOTAL |

5.4 |

6.9 |

6.1 |

6.3 |

7.3 |

6.9 |

Source: LR 455 Survey

Despite Nebraska's low-cost power and indications of relative consumer satisfaction with the quality of electric service, there is a certain amount of interest in retail competition and customer choice of electric supplier.

3.2.1 Large Consumers

Interest in retail competition is judged to be primarily among large industrial firms, chain store and business organizations. Competitive suppliers typically market to large users with high load factors, or commercial chain stores with central billing, or easy access to larger commercial consumers through business organizations.

A small segment of Nebraska's larger 2,300 industrial users and 100,000 commercial customers have already begun to "supply shop" prior to any retail market being established. Suppliers have reportedly signed contracts with some agricultural consumers, large industrial users and chain store organizations with terms which state: When retail competition is available in Nebraska, [the supplier] will have the first right of refusal for electrical service.

Although competitive prices may only offer fractions of a cent per kilowatt hour reduction, large customers can gain substantial savings due their volume of use. Competitive suppliers may also offer "loss-leader" rates to acquire a new customer. While private suppliers can offer such discriminatory pricing, Nebraska public power systems are prevented by law from providing power to large consumers at discount prices. Pricing must be set to cost-of- service and rate classes must be established to prevent discrimination. This is intended to avoid cost-shifting to smaller commercial and residential consumers.

Electric industry restructuring laws and rules in other states prohibit cost-shifting from large to small consumers, but the manner in which the competitive market functions can produce that result regardless of regulatory intent. As illustrated by the experience in other states, all markets have opened for large consumers first, either through phasing of implementation, or through the market opportunities allowed to suppliers to choose their customers. However, all consumers are required to pay the costs for the transition to competition, even though no supplier may wish to serve them at this time.

3.2.2 Residential and Small Consumers

"Customer choice" marketing implies every electric consumer will have an opportunity to choose a supplier. In response to such marketing, some residential consumers have shown interest in retail competition. UtiliCorp conducted a survey of its Nebraska natural gas customers in 1997 and found that for a savings of 5 percent on total billing: 24 percent of customers stated they would be "very likely" to switch electric companies; 31 percent would be "somewhat likely" to switch; 22 percent would be "somewhat unlikely"; 20 percent would be "very unlikely"; 2 percent did not know.

Other indications have come from customer satisfaction surveys to determine overall effectiveness in meeting customer needs and to assist in identifying areas of customer service needing improvement. Such surveys sometimes include questions that attempt to identify the extent to which customers might be lured away by competing electric service providers under a retail competition environment.

One such survey was commissioned by the Nebraska Public Power District (NPPD) during 1998 which showed that nearly 90 percent of its residential customers found NPPD's service to be either satisfactory or very satisfactory. However, when asked if they would switch to another electric provider if offered a 5 percent price break, about one third of the residential customers said that they would switch. Almost one-half of the customers said they would switch providers for a 10 percent savings and about two-thirds said they would switch if offered a 15 percent savings.

Marketing experts do not regard such hypothetical questions regarding the extent to which customers might switch providers as a reliable indicator of how customers would actually respond in a competitive retail environment. Several studies have noted that most consumers have not switched their long distance telephone carrier, despite more than 10 years of competition and intensive mass media advertising.

The same consumer caution is evident in the early electric markets. Following extensive marketing efforts in Palm Springs, California which cost an estimated $330 per customer, Enron canceled an aggregation effort after only 8 percent of customers responded. In Pennsylvania, where three to four million customers were eligible for a competitive supplier, 1.8 million signed up by submitting a postcard, and 400,000, or 10 percent of the total eligible, were estimated to have changed supplier.

In Nebraska, despite indications of polls, support for retail competition is not consistent across the state. Rural consumers, in particular, are judged to have much less interest in retail competition, based in part on experience with deregulation of other industries in rural areas and relative satisfaction with existing electric service. Although no specific survey has been conducted of Nebraska's rural consumers, a study of potential impacts on rural Kansas electric consumers has found: "Like all expansion of trade opportunities, some customers will benefit, while others will be adversely affected. . . An unintended consequence is to change the existing price structure of distributing electricity, both within and among rate classes. The result is new social policy that does not benefit most rural customers." This study projected widespread rate increases and possible impacts reaching into local economies, taxation bases, and economic development.

Full access in the market and residential and small commercial consumer behavior for competitive electric service could take many years to develop. In the meantime, competitive suppliers are working to establish a base among consumers by enhancing the attractiveness of switching suppliers in a number of ways. One method is to expand an existing customer relationship by offering packages of services including natural gas, energy efficiency, telephone, Internet, cable television, home security, and other services extending to lawn care and appliance repair.

Nationally, it has been noted that electric, natural gas, and telecommunications utilities are moving rapidly to transform themselves into delivery companies that offer their customers a range of products packaged in combination with electric energy. Convergence with other "wires" and energy businesses is viewed by many as the next horizon in marketing. To position themselves to offer multi-service packages to consumers many electric utilities are adding or acquiring new operations, or developing alliances with telephone companies, satellite entertainment companies, Internet providers, and other businesses. While existing relationships with customers for natural gas or telecommunications services provide an entree and profits from these other services may help to offset low profits from electric service, it is not clear that consumers are ready for this transformation.

One recent study has noted that residential electric consumers seem to be sending their utilities a clear, consistent message: they are most interested at this point in purchasing those products and services that are directly related to their electric supplier's core business. A narrowly focused interest in energy-related products and services seems to suggest that consumers are not convinced that their electric supplier has expertise in anything other than electricity.

The study also noted: "Even though many electric suppliers may be well-positioned to offer other services that can be run through electric lines, such as telephone or cable/satellite television services, most residential consumers are unaware of these possibilities."

The study reported that 25 percent of consumer surveyed said they would consider purchasing Internet services; 28 percent of those surveyed said they were likely to purchase telephone service from their electric company; and 40 percent said they would consider buying cable television service.

Multi-service packages for Nebraska have gotten a mixed response thus far. In 1997, Utilicorp and PECO combined their operations to offer "Energy One" providing a range of services. However, after reportedly expending more than $1 million and acquiring an insufficient consumer base, the business was suspended.

More successful has been the KN "choice" natural gas program. Through its advertising, KN has promoted choice for all energy supplies, and initially implied an opportunity to expand into electric choice a through agreements with municipalities without passage of state legislation. While the core KN service remains gas at this time, the KN gas program is connected with a range of other services from DISH Network. a satellite entertainment company; Metricon. an Internet service provider; MaxServe. a home products repair service; Frontier. a long distance telephone service; and DQE. and energy efficiency company for natural gas services. The KN program may directly impact future choice programs in electricity.

The mixed consumer response to multi-service packages indicates increased risk for those who invest early in alliances or acquisitions for multi-service efforts. However, such investments may provide a supplier with a foothold in a market otherwise served by consumer-owned systems, or may provide a competitive position for a consumer-owned system.

State and local policies related to choice in "wires" and energy services need to acknowledge that opportunities created in one type of service may shape the options for electric service through multi-service packages. A comprehensive approach to competition in all services needs to be considered.

Realities of Retail Competition and Customer Choice for Electricity

As indicated in other states, the market can be expected to move in advance of, and in some cases pre-empt, policy-making. Just as the Federal Trade Commission staff has cautioned FERC that structure is more important than behavioral rules in the wholesale market, the same is apparent for the retail market.

For retail competition to provide benefits for all consumers, close attention needs to be given to structural issues and rules. For Nebraska this means: 1) transparent costs/transparent pricing; 2) default and standard offer service; 3) marketer certification and market power restrictions; 4) competitive options and leverage for consumers; 5) viable transaction process and protocols; 6) metering and billing policies; 7) adequate consumer education and protection; 8) safety net for small and rural consumers. Policies and physical infrastructure needed for these elements should be in place prior to the opening of a retail market. In addition there must be a recognition that rules and protections will need to evolve with the market.

3.4.1 Transparent Costs and Transparent Pricing

For competitive markets to function, it is essential to have clear information on costs and pricing in order for consumers to make informed decisions. Identification of costs is usually accomplished by "unbundling" a consumer bill. This is achieved by a utility undertaking an accounting procedure and providing line items on a consumer bill that break out the costs of transmission, distribution, and the energy charge that is subject to competition, as well as other charges that may include energy efficiency, renewable energy, or public benefits.

Equally important is transparent pricing. requiring that prices for wholesale power, and prices for electric energy provided under retail contracts be public information that is provided in a manner that is easily accessible and timely. Private transactions with secret pricing will serve to undermine a competitive market and promote discrimination and other market abuses.

3.4.2 Default and Standard Offer Service

All states opening retail competition have developed a fallback option. or provider of last resort. for consumers who cannot, or choose not to, have a competitive power supplier. Incumbent utility providers are commonly designated as the provider of "default" or "standard offer service", although the state of Maine intends to bid out service for all default customers. Other states, such as Massachusetts, are considering setting "default" prices at the average rate for the ISO New England. The common problem noted in Chapter Two is that standard offer or default rates initially set by regulators below market prices can undermine a fledgling retail market. To provide these consumers with some degree of benefit, this form of service is usually accompanied by a rate cap or mandatory rate reduction. Nebraska's low power costs, however, may preclude such reductions or rate caps.

3.4.3 Marketer Certification and Market Power Restrictions

Requirements for every retail marketer to be certified for service to retail customers, and adhere to established standards and rules for service to consumers, have become common elements of state restructuring plans. Lacking in many state plans, however, are restrictions on relationships of retail marketers to suppliers. Markets can be undermined though exclusive relationships between a supplier and a retail marketer or broker. Such exclusive relationships, as well as requirements on disclosure of corporate or contractual relationships in the certification process should be required. The market also requires the presence of enough retail marketers to create real choice for consumers. An insufficient number of capable retail marketers can create a situation in which consumer are forced to compete against one another for service from limited suppliers.

3.4.4 Competitive Options and Leverage for Consumers

It is essential that consumers have leverage to balance the influence of suppliers in the marketplace, and that they possess viable options to utilize that leverage. As indicated in the states that have established competitive retail markets, residential and small commercial customers have not gained full access to competitive suppliers to date. The focus on large customers and "cherry-picking" that has evolved in other states creates danger of cost-shifting from large to small consumers. Additionally, disaggregation of local loads with good diversity and load factors created by "cherry-picking" is likely to delay or make it more costly and difficult for small consumers to receive competitive supply. Policy decisions to "phase" the entrance of customers into the competitive market, allowing larger customers first, can institutionalize this problem. To address this issue, one state. New Mexico. has proposed to allow small consumers into the market first. However, depending upon the response of marketers, this could merely delay the opening of a full market for retail competition and defer the disaggregation temporarily.

While "customer choice" means in theory that every individual customer will have the opportunity to choose a supplier, the reality is that most consumers will need to be joined together or "aggregated" to receive attention of competitive suppliers. Aggregation reduces transaction costs and increases consumer leverage. Aggregation can be undertaken in such a way that large and small consumers benefit as a result of the diversity of the total aggregated load and pricing addressing their individual load characteristics within the total load.

While consumers need to have options for all types of aggregation, it has been recognized in other states that certain forms of aggregation offer greater leverage and opportunities for savings, services, and control for consumers than other forms of aggregation. The hierarchy of leverage provided by various types of aggregation is fairly clear:

Public power systems, municipalities and rural cooperatives that own distribution systems and already purchase supplies in the competitive wholesale market offer the most joint opportunity for aggregation and market leverage. They also offer the greatest opportunity to reduce transaction costs. the duplication of billing, collection and accounting functions needed by a competitive supplier, in addition to the competitive supplier's advertising or customer acquisition and retention costs.

Local governments that utilize their franchise powers to contract for electric service, or aggregate consumers for energy supply, but do not own distribution systems, offer the next level of opportunities and leverage for consumers in a competitive marketplace. This does not reduce transaction costs to the same extent as a public power or cooperative systems, but can reduce competitive customer acquisition and retention costs.

Consumer-oriented buying clubs or organizations offer the next level of market leverage and opportunities, but do not substantially reduce transaction costs.

Private brokers offer the least opportunity and leverage for consumers, and similar to buying clubs do not reduce transaction costs and charge added fees that may amount to up to 25 percent of consumer savings.

3.4.5 Transaction Process and Protocols

Business transaction process and protocols must be established that allow transition of consumers and their account data, as well as funds between marketers or suppliers and local distribution providers conducting the metering and billing. Physically, this requires computer systems and software that are compatible and capable of easy exchange of data and information. In terms of policy, it requires policy decisions on steps for customer transition, the types of verification for customer account transfer required, the timing allowed for customer transfer, and considerations for protection of proprietary information. Substantial inequities may exist in current requirements between disclosure of information by public and private market providers which would need to be addressed in the transaction protocols.

3.4.6 Metering and Billing Policies

In most states it has been assumed that metering, billing and collections will be carried out by the existing local distribution company. However, options for types of billings, frequency of meter readings, and types of metering also need to be determined. Capability of the local distribution companies in this arena, especially as the market advances, would need to be assessed and perhaps new combined efforts undertaken.

3.4.7 Consumer Education and Protection

Consumer education and consumer protection are fundamental elements of a retail market. However, education programs and protection rules cannot substitute for an inadequate market structure that is unbalanced, or make up for a lack of consumer options and leverage and basic protections concerning market power.

3.4.7.1 Consumer Education

Consumer education undertaken by the open-market states has been extensive. A full education program includes: 1) direct market data and information provided to a consumer; 2) mass media advertising and printed materials; 3) public speaking and workshops for target groups; 4) training of state and local employees who have contact with consumers. The programs often being prior to the market-open date and are divided into start-up and on-going operations intended to keep consumers up-to-date with changes in the market. Although important distinctions must be made between marketing and education, all market participants must take part in consumer education and be willing to disseminate unbiased materials prepared by the state, or private vendor hired by the state.

3.4.7.1.1 Direct Market Data and Information

Direct market data and information includes bills inserts and other educational pieces provided to each metered customer. While certain bill inserts prepared by the state may cover general information concerning a retail electric market, a consumer's bill is the central data document.

Unbundling of costs of electric service displayed on a consumer's bill each month provides consumers with the price of energy a competitive supplier must beat to provide savings, and an understanding of the fixed costs for transmission, distribution, and other charges related to service delivery.

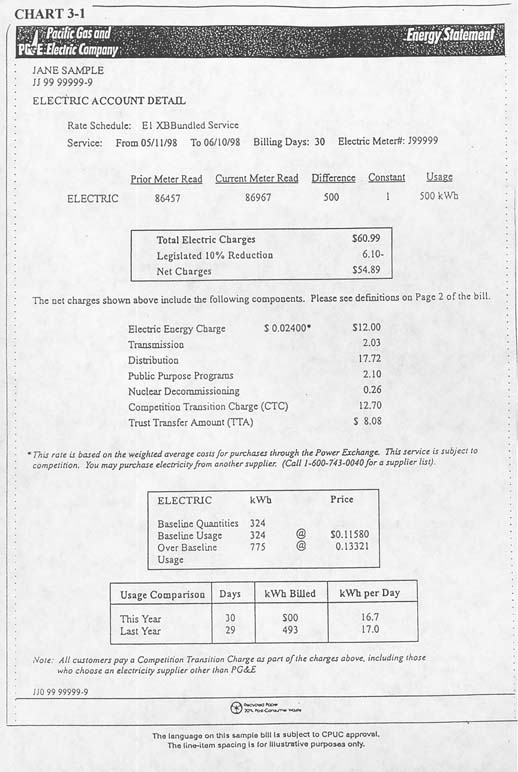

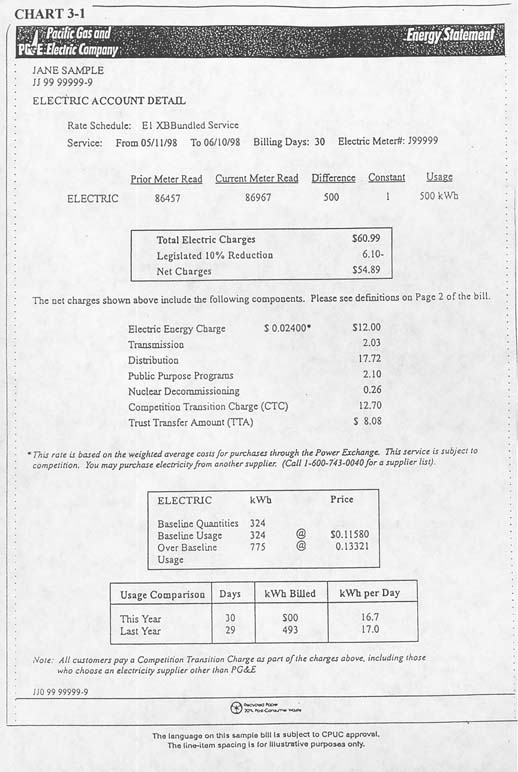

Chart 3-1

A second educational document that can be provided to consumers as a bill insert is a "label" indicating: resource mix of the power supply, emissions data, wholesale price, and labor or other key factors related to power supply. As of June 1999, 13 states had legislative requirements for consumers to received such a label; six states had established this requirement through regulatory orders. (See Chapter 6, section 6.3.2.4 for a discussion of "consumer labels" and Chart 6-1 in Chapter 6 for a sample label.)

3.4.7.1.2 Funding of Educational Programs

Funding for education programs is commonly included as a customer charge. California has reportedly allocated $89 million for a three-pronged consumer education effort. Massachusetts spent $1.8 million in start-up funds in fiscal year 1998/99 and plans $655,000 in 1999/2000. New York similarly spent $1 million as part of the Consumer Protection Board budget in fiscal year 1998/99 and plans $1 million for fiscal year 1999/2000, additional funds were expended by the state Public Service Commission. Ohio has reportedly allocated $33 million for a five year period ($1.30 per customer per year) for consumer education.

If Nebraska's spending were consistent with that of Ohio ($1.30 per customer per year) consumers might expect to pay $1million for an education program annually throughout a multi-year transition period. This would be an added kilowatt hour charge for all consumers.

3..4.7.2 Consumer Protection

Consumer protection typically includes policies and rules concerning: customer slamming, cramming and telemarketing prohibitions; deceptive practices prohibitions; discrimination and anti-redlining prohibitions; data confidentiality; product disclosure requirements (or labeling); customer complaint and dispute resolution provisions; low income protections; payment sequence and termination requirements; limitations on fees; and reporting and data collection requirements.

For Nebraska, local governments have maintained the role of developing and implementing consumer protection policies. Consumer-owned systems are based on the principle that every customer is entitled to receive electric service at rates which recover all costs of providing such services and which do so fairly, equitably and without discrimination among customers. Application of these policies may vary among local systems.

In a competitive retail market, statewide standards and policies would be needed.

Statewide policies for consumers in a competitive retail market could be based in part on a uniform "Consumer Bill of Rights." (See Table 3-3 for sample.)

3.4.7.3 Safety Net

In addition to funds for education programs and protection for low-income and other consumers, rural states such as Nebraska may require a "safety net" to offset detrimental economic effects of retail competition. The USDA study noted earlier estimates that a national rural safety net starting at a cost of $1 billion annually in 2000 and rising to $2.4 billion by 2015 will be required. Nebraska was among 19 states noted by the USDA study that would suffer net economic losses. A full assessment of potential impacts indicated by the USDA study would need to be evaluated for Nebraska to assess the need for, or the amount of, a state "safety net."

Designation and Development of a State Regulatory Body to Augment Local Control

In order to assure necessary evaluations take place and development, implementation, and enforcement of standard policies and rules, a statewide agency would need to be designated, authorized and funded to augment local regulatory functions. Rules and standards concerning the issues outlined above may be developed by workgroups in combination with a state regulatory body with professional support staff.

Nebraska's system of local regulatory control has served consumers well within a monopoly non-profit, cost-of-service market structure. However, designation and development of a state regulatory body to augment local regulatory control would be essential for a competitive retail market. The dividing line between local and state authority could be drawn to allow public formulation of statewide uniform policies and standards, and local implementation of such policy and standards for those systems perceiving benefits and choosing to participate in retail competition. Limited pre-market standards and policies might also be applied to all systems, such as the need to conduct an accounting to unbundle transmission, distribution and electric energy charges in the bills of each consumer class.

During a preparation stage, the Nebraska Power Review Board could be authorized by the legislature to assist with coordination of work groups made up of industry representatives and other stakeholders who would develop proposed rules for: 1) Marketer Certification; 2) Transaction Process and Protocols; 3) Consumer Education; 4) Consumer Protection; 5) Default or Standard Offer Service; 6) Stranded Cost/Stranded Benefits Quantification and Recovery; 7) Other Consumer and Retail Market Issues; 9) Detailed Implementation Legislation that would include the rules and results of studies. (See sections 9.1.3 and 9.1.4 for a full listing of rules, standards and policies to be developed.)

In addition to participation in the work groups, local consumer-owned systems could undertake unbundling of costs, and develop coordinated policies for metering, billing, and collection, as well as examine and undertake opportunities to gain greater operational efficiencies.

Joint study efforts between local systems and the state agency could include examination of opportunities for: 1) greater transmission efficiencies; 2) retaining low cost wholesale supply; 3) a Nebraska transaction center; 4) threshold cost/benefit analysis, (all of these are described in detail in Chapter 5) and 5) the possible need for "safety net" funds.

This process for development of rules and follow-on studies could take place while a regional ISO or RTO, and new wholesale market are in formation. When regional wholesale market prices indicate possible benefits over Nebraska prices and these other structural pre-conditions are deemed to be in place, the state agency could hold hearings to determine whether the implementation legislation should be enacted.

If retail competition is implemented, those systems wishing to participate could opt-in through a public process at the local level.

In the implementation phase, a regulatory agency would be authorized to enforce standards, rules and guidelines, and to investigate violations on an on-going basis. Designation and development of what agency would undertake this implementation role remains uncertain.

Advisory Group and Task Positions on Key Issues

During the summer and fall of 1998, one subcommittee of the LR 455 Advisory Group met to address key questions and issues related to Retail Competition and a second subcommittee met to discuss key questions and issues related to Customer Choice and Consumer Protection. Summaries of their discussions were brought back to the full Advisory Group. The results of those discussion are summarized below.

1) The subcommittees and the Advisory Group generally agreed with experience elsewhere that consumer interest in retail competition was primarily among large industrial firms, and commercial and chain store organizations.

2)There was also consensus that new suppliers are most interested in serving larger customers.

3) Within both the subcommittees and the full Advisory Group there was general consensus that there would be winners and losers in retail competition and that retail competition would negatively affect small rural consumers in Nebraska. Small consumers in urban areas could also be negatively affected. There was also general agreement that rather than rural vs. urban, a customer's load characteristics would determine whether or not they would benefit.

4) There was disagreement on whether different classes of consumers could be protected in a competitive retail market. While protection for quality of service might be possible, protection against price increases might not be. Although a statewide public service commission and public consumer advocates might be necessary, several members believed that "true competition" was the most important method to protect consumers. Unbundling generation and transmission was viewed as the first step toward retail competition.

5) Local control and non-discriminatory service was viewed by some Advisory Group members as the best way to protect low-income consumers. Others believed that a uniform system of state regulation would be preferable to local regulation which could apply inconsistent rules and standards.

6) The subcommittees believe the best methods to assure that retail competition would not result in cost shifting from large to small consumers would be utilization of price caps, mandatory rate reductions, or have residential consumers receive competitive low-cost power first. Without such mechanisms, it was expected that some consumers would suffer. However, proposals for use of the mechanisms suggested were not acceptable to many members of the Advisory Group.

7) The subcommittees proposed that the best way to assure universal service--wired connection of all consumers desiring service--under retail competition would be to have mechanisms in place that provide safety nets. Some members of the Advisory Group disagreed. "Obligation-to-serve"-- the obligation to have enough power to serve everyone who is connected. was also questioned as a responsibility of the local system in a competitive retail environment.

8) In order to protect against predatory pricing and cherry-picking, the subgroup believed that state regulation would be required. It was noted by Advisory Group members that discrimination in pricing to preferred large customers was also a problem under the current system, although prices were set by class. However, predatory pricing and cherry-picking could be the norm rather than the exception in a competitive retail market.

9) The subcommittees believed the best method to prevent deterioration in quality of service and reliability is to remain responsive to constituents. Local boards still want reliability and will want to make sure rates will be set to recover sufficient funds to maintain and enhance the local distribution system.

10) It was agreed that the state would need a major consumer education program if retail competition were established. The difference between marketing and education was noted. The Advisory Group had consensus on a non-biased program that would focus on why consumers had choice rather than "who to choose" Fees would be assessed on kilowatt hour charges to fund a program by an unbiased third party.

11) The subcommittees proposed that a statewide regulatory body be put in place to promulgate, oversee, and enforce new rules if retail competition were established. It was noted that that local control can exist without giving up anything to state regulation; one is not exclusive of the other. In general, the majority was leaning toward some statewide authority, but still reiterated that the topic was premature for 1999-2000. Suggestions were made to start with identification of the consumer protections needed, then decide if these were local or statewide issues.

12) The subcommittees and the Advisory Group had no recommendation on whether the Power Review Board of the Public Service Commission, or a new state entity would be the best body for statewide regulation.

Summary of Key Points

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, conditions in Nebraska differ significantly from those of other states that are moving to establish retail competition. The state is served almost exclusively by non-profit consumer-owned electric systems under local control. While retail competition targets electric energy pricing, wholesale power costs for Nebraska systems are already below those of the region and are expected to remain so.

However, possible changes in wholesale power supply costs and pressures for retail competition may make it impossible for Nebraska systems to maintain low cost pricing. It is essential, therefore to examine all options for retail competition and methods to protect Nebraska consumers.

Recommendation: In order to fully protect consumers, the Task Force recommends that structure and uniform rules for a retail market be in place prior to competition. As described in Chapter 5, the Nebraska Power Review Board could coordinate development of rules, standards, and examinations of options during a preparation stage. A statewide regulatory body would need to be designated to augment local control to help develop and enforce those rules in an implementation stage.

There are variant options the state may pursue to address retail competition ranging from modification of the industry's Current Structure, to Limited Access to competitive suppliers, to full Open Access to competitive suppliers.

The following chapter describes those three models and the key questions raised by each model.